HTTP

Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP) is an application-layer protocol for transmitting hypermedia documents, such as HTML. It was designed for communication between web browsers and web servers, but it can also be used for other purposes. HTTP follows a classical client-server model, with a client opening a connection to make a request, then waiting until it receives a response. HTTP is a stateless protocol, meaning that the server does not keep any data (state) between two requests. Though often based on a TCP/IP layer, it can be used on any reliable transport layer; that is, a protocol that doesn't lose messages silently, such as UDP.

Requests

The messages sent by the client, usually a Web browser, are called Requests.

Response

The messages sent by the server as an answer are called Responses.

Recipient || User Agent

Recipients or User Agents are the clients which makes the request. Most of the time it is a browser. But sometimes it can be something else, like a Crawler, Software, server(server makes request to another server) etc.

Components of HTTP-based systems

HTTP is a client-server protocol: requests are sent by one entity, the user-agent (or a proxy on behalf of it). Most of the time the user-agent is a Web browser, but it can be anything, for example a robot that crawls the Web to populate and maintain a search engine index.

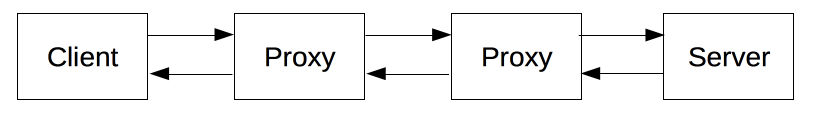

Each individual request is sent to a server, which will handle it and provide an answer, called the response. Between this request and response there are numerous entities, collectively designated as proxies, which perform different operations and act as gateways or caches, for example.

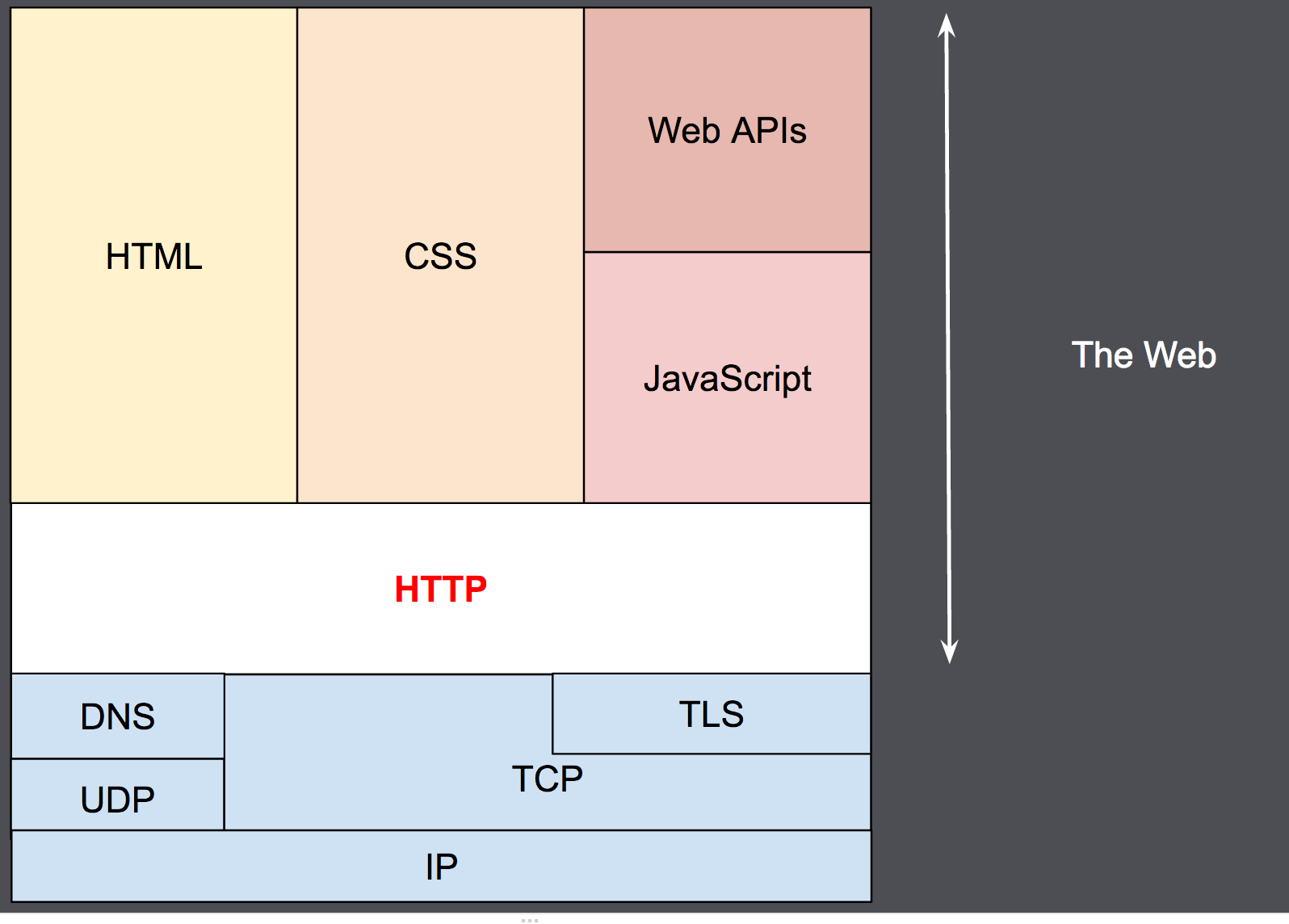

In reality, there are more computers between a browser and the server handling the request: there are routers, modems, and more. Thanks to the layered design of the Web, these are hidden in the network and transport layers. HTTP is on top at the application layer. Although important to diagnose network problems, the underlying layers are mostly irrelevant to the description of HTTP.

Client: the user-agent

The user-agent is any tool that acts on the behalf of the user. This role is primarily performed by the Web browser; a few exceptions being programs used by engineers, and Web developers to debug their applications.

The browser is always the entity initiating the request. It is never the server (though some mechanisms have been added over the years to simulate server-initiated messages).

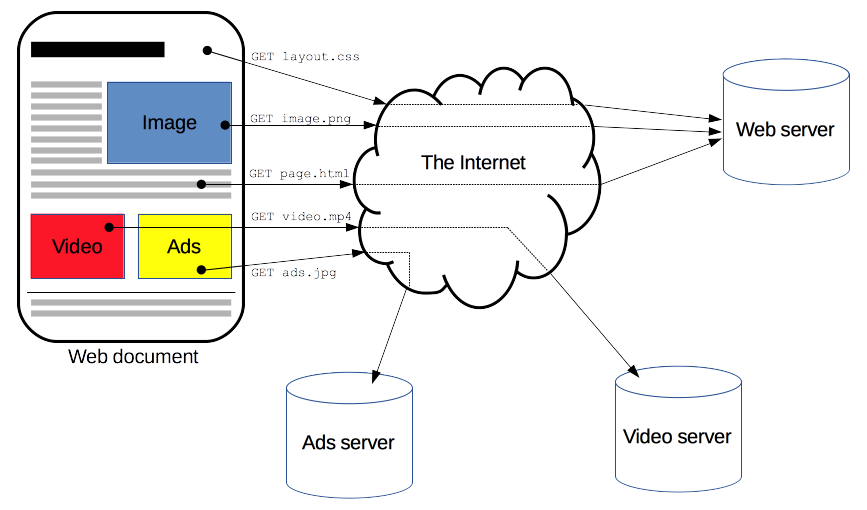

To present a Web page, the browser sends an original request to fetch the HTML document from the page. It then parses this file, fetching additional requests corresponding to execution scripts, layout information (CSS) to display, and sub-resources contained within the page (usually images and videos). The Web browser then mixes these resources to present to the user a complete document, the Web page. Scripts executed by the browser can fetch more resources in later phases and the browser updates the Web page accordingly.

A Web page is a hypertext document. This means some parts of displayed text are links which can be activated (usually by a click of the mouse) to fetch a new Web page, allowing the user to direct their user-agent and navigate through the Web. The browser translates these directions in HTTP requests, and further interprets the HTTP responses to present the user with a clear response.

The Web server

On the opposite side of the communication channel, is the server which serves the document as requested by the client. A server presents only as a single machine virtually: this is because it may actually be a collection of servers, sharing the load (load balancing) or a complex piece of software interrogating other computers (like cache, a DB server, e-commerce servers, …), totally or partially generating the document on demand.

A server is not necessarily a single machine, but several servers can be hosted on the same machine. With HTTP/1.1 and the Host header, they may even share the same IP address.

Proxies

Between the Web browser and the server, numerous computers and machines relay the HTTP messages. Due to the layered structure of the Web stack, most of these operate at either the transport, network or physical levels, becoming transparent at the HTTP layer and potentially making a significant impact on performance. Those operating at the application layers are generally called proxies. These can be transparent, or not (changing requests going through them), and may perform numerous functions:

- Caching (the cache can be public or private, like the browser cache)

- Filtering (like an antivirus scan, parental controls, …)

- Load balancing (to allow multiple servers to serve the different requests)

- Authentication (to control access to different resources)

- Logging (allowing the storage of historical information)

HTTP is stateless, but not sessionless

HTTP is stateless: there is no link between two requests being successively carried out on the same connection. This immediately has the prospect of being problematic for users attempting to interact with certain pages coherently, for example, using e-commerce shopping baskets. But while the core of HTTP itself is stateless, HTTP cookies allow the use of stateful sessions. Using header extensibility, HTTP Cookies are added to the workflow, allowing session creation on each HTTP request to share the same context, or the same state.

What can be controlled by HTTP

This extensible nature of HTTP has, over time, allowed for more control and functionality of the Web. Cache or authentication methods were functions handled early in HTTP history. The ability to relax the origin constraint, by contrast, has only been added in the 2010s.

Here is a list of common features controllable with HTTP.

Cache: How documents are cached can be controlled byHTTP. The server can instruct proxies, and clients, what to cache and for how long. The client can instruct intermediate cache proxies to ignore the stored document.Relaxing the origin constraint: To prevent snooping and other privacy invasions, Web browsers enforce strict separation between Web sites. Only pages from the same origin can access all the information of a Web page. Though such constraint is a burden to the server,HTTPheaders can relax this strict separation server-side, allowing a document to become a patchwork of information sourced from different domains (there could even be security-related reasons to do so).Authentication: Some pages may be protected so only specific users can access it. Basic authentication may be provided byHTTP, either using the WWW-Authenticate and similar headers, or by setting a specific session usingHTTPcookies.Proxy and tunneling: Servers and/or clients are often located on intranets and hide their true IP address to others.HTTPrequests then go through proxies to cross this network barrier. Not all proxies areHTTPproxies. The SOCKS protocol, for example, operates at a lower level. Others, like ftp, can be handled by these proxies.Sessions: UsingHTTPcookies allows you to link requests with the state of the server. This creates sessions, despite basicHTTPbeing a state-less protocol. This is useful not only for e-commerce shopping baskets, but also for any site allowing user configuration of the output.