Transparent caching

Let’s say we have a function slow(x) which is CPU-heavy, but its results are stable. In other words, for the same x it always returns the same result. If the function is called often, we may want to cache (remember) the results for different x to avoid spending extra-time on recalculations. But instead of adding that functionality into slow() we’ll create a wrapper. As we’ll see, there are many benefits of doing so. Here’s the code, and explanations follow:

function slow(x) {

// there can be a heavy CPU-intensive job here

alert(`Called with ${x}`);

return x;

}

function cachingDecorator(func) {

let cache = new Map();

return function(x) {

if (cache.has(x)) { // if the result is in the map

return cache.get(x); // return it

}

let result = func(x); // otherwise call func

cache.set(x, result); // and cache (remember) the result

return result;

};

}

slow = cachingDecorator(slow);

alert( slow(1) ); // slow(1) is cached

alert( "Again: " + slow(1) ); // the same

alert( slow(2) ); // slow(2) is cached

alert( "Again: " + slow(2) ); // the same as the previous line

In the code above cachingDecorator is a decorator: a special function that takes another function and alters its behavior. The idea is that we can call cachingDecorator for any function, and it will return the caching wrapper. That’s great, because we can have many functions that could use such a feature, and all we need to do is to apply cachingDecorator to them.

By separating caching from the main function code we also keep the main code simpler. Now let’s get into details of how it works.

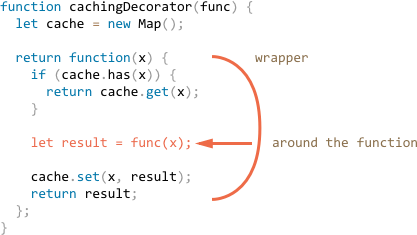

The result of cachingDecorator(func) is a “wrapper”: function(x) that “wraps” the call of func(x) into caching logic:

As we can see, the wrapper returns the result of func(x) “as is”. From an outside code, the wrapped slow function still does the same. It just got a caching aspect added to its behavior.

To summarize, there are several benefits of using a separate cachingDecorator instead of altering the code of slow itself:

- The

cachingDecoratoris reusable. We can apply it to another function. - The caching logic is separate, it did not increase the complexity of

slowitself (if there were any). - We can combine multiple decorators if needed (other decorators will follow).

func.call()

The caching decorator mentioned above is not suited to work with object methods. For instance, in the code below worker.slow() stops working after the decoration:

// we'll make worker.slow caching

let worker = {

someMethod() {

return 1;

},

slow(x) {

// actually, there can be a scary CPU-heavy task here

alert("Called with " + x);

return x * this.someMethod(); // (*)

}

};

// same code as before

function cachingDecorator(func) {

let cache = new Map();

return function(x) {

if (cache.has(x)) {

return cache.get(x);

}

let result = func(x); // (**)

cache.set(x, result);

return result;

};

}

alert( worker.slow(1) ); // the original method works

worker.slow = cachingDecorator(worker.slow); // now make it caching

alert( worker.slow(2) ); // Whoops! Error: Cannot read property 'someMethod' of undefined

The error occurs in the line (*) that tries to access this.someMethod and fails. Can you see why?

The reason is that the wrapper calls the original function as func(x) in the line (**). And, when called like that, the function gets this = undefined.

We would observe a similar symptom if we tried to run:

let func = worker.slow; func(2); // Whoops! Error: Cannot read property 'someMethod' of undefined

So, the wrapper passes the call to the original method, but without the context this. Hence the error.

Let’s fix it. There’s a special built-in function method func.call(context, …args) that allows to call a function explicitly setting this. The syntax is:

func.call(context, arg1, arg2, ...)

It runs func providing the first argument as this, and the next as the arguments. To put it simply, these two calls do almost the same:

func(1, 2, 3); func.call(obj, 1, 2, 3)

They both call func with arguments 1, 2 and 3. The only difference is that func.call also sets this to obj.

As an example, in the code below we call sayHi in the context of different objects: sayHi.call(user) runs sayHi providing this=user, and the next line sets this=admin:

function sayHi() {

alert(this.name);

}

let user = { name: "John" };

let admin = { name: "Admin" };

// use call to pass different objects as "this"

sayHi.call( user ); // this = John

sayHi.call( admin ); // this = Admin

And here we use call to call say with the given context and arguments:

function say(phrase) {

alert(this.name + ': ' + phrase);

}

let user = { name: "John" };

// user becomes this, and "Hello" becomes the first argument

say.call( user, "Hello" ); // John: Hello

In our case, we can use call in the wrapper to pass the context to the original function:

let worker = {

someMethod() {

return 1;

},

slow(x) {

alert("Called with " + x);

return x * this.someMethod(); // (*)

}

};

function cachingDecorator(func) {

let cache = new Map();

return function(x) {

if (cache.has(x)) {

return cache.get(x);

}

let result = func.call(this, x); // "this" is passed correctly now

cache.set(x, result);

return result;

};

}

worker.slow = cachingDecorator(worker.slow); // now make it caching

alert( worker.slow(2) ); // works

alert( worker.slow(2) ); // works, doesn't call the original (cached)

Now everything is fine. To make it all clear, let’s see more deeply how this is passed along:

- After the decoration

worker.slowis now the wrapperfunction (x) { ... }. - So when

worker.slow(2)is executed, the wrapper gets 2 as an argument andthis=worker(it’s the object before dot). - Inside the wrapper, assuming the result is not yet cached,

func.call(this, x)passes the currentthis(=worker) and the currentargument(=2) to the original method.

func.apply()

Now let’s make cachingDecorator even more universal. Till now it was working only with single-argument functions. Now how to cache the multi-argument worker.slow method?

let worker = {

slow(min, max) {

return min + max; // scary CPU-hogger is assumed

}

};

// should remember same-argument calls

worker.slow = cachingDecorator(worker.slow);

We have two tasks to solve here.

- First is how to use both arguments

minandmaxfor the key in cachemap. Previously, for a single argumentxwe could justcache.set(x, result)to save the result andcache.get(x)to retrieve it. But now we need to remember the result for a combination of arguments (min,max). The native Map takes single value only as the key. - The second task to solve is how to pass many arguments to

func. Currently, the wrapperfunction(x)assumes a single argument, andfunc.call(this, x)passes it.

There are many solutions possible.

- Implement a new (or use a third-party) map-like data structure that is more versatile and allows multi-keys.

- Use nested maps:

cache.set(min)will be a Map that stores the pair(max, result). So we can get result ascache.get(min).get(max). - Join two values into one. In our particular case we can just use a string

"min,max"as the Map key. For flexibility, we can allow to provide a hashing function for the decorator, that knows how to make one value from many.

For many practical applications, the 3rd variant is good enough, so we’ll stick to it. Here we can use another built-in method func.apply.

func.apply(context, args);

It runs the func setting this=context and using an array-like object args as the list of arguments. For instance, these two calls are almost the same:

func(1, 2, 3); func.apply(context, [1, 2, 3])

Both run func giving it arguments 1,2,3. But func.apply also sets this=context. For instance, here say is called with this=user and messageData as a list of arguments:

function say(time, phrase) {

alert(`[${time}] ${this.name}: ${phrase}`);

}

let user = { name: "John" };

let messageData = ['10:00', 'Hello']; // become time and phrase

// user becomes this, messageData is passed as a list of arguments (time, phrase)

say.apply(user, messageData); // [10:00] John: Hello (this=user)

The only syntax difference between call and apply is that call expects a list of arguments, while apply takes an array-like object with them.

You can use spread operator on call to get the same effect as apply. These two calls are almost equivalent:

let args = [1, 2, 3]; func.call(context, ...args); // pass an array as list with spread operator func.apply(context, args); // is same as using apply

If we look more closely, there’s a minor difference between such uses of call and apply.

callonly works when you use the argument with spread operator and argument is iterable type.applyonly works on array-like object.

And if args is both iterable and array-like, like a real array, then we technically could use any of them, but apply will probably be faster, because it’s a single operation. Most JavaScript engines internally optimize is better than a pair call + spread.

One of the most important uses of apply is passing the call to another function, like this:

let wrapper = function() {

return anotherFunction.apply(this, arguments);

};

That’s called Call Forwarding. The wrapper passes everything it gets: the context this and arguments to anotherFunction and returns back its result.

When an external code calls such wrapper, it is indistinguishable from the call of the original function.

Now let’s bake it all into the more powerful cachingDecorator:

let worker = {

slow(min, max) {

alert(`Called with ${min},${max}`);

return min + max;

}

};

function cachingDecorator(func, hash) {

let cache = new Map();

return function() {

let key = hash(arguments); // (*)

if (cache.has(key)) {

return cache.get(key);

}

let result = func.apply(this, arguments); // (**)

cache.set(key, result);

return result;

};

}

function hash(args) {

return args[0] + ',' + args[1];

}

worker.slow = cachingDecorator(worker.slow, hash);

alert( worker.slow(3, 5) ); // works

alert( "Again " + worker.slow(3, 5) ); // same (cached)

Now the wrapper operates with any number of arguments.

Borrowing a method

In JavaScript, sometimes it’s desirable to reuse a function or method on a different object other than the object or prototype it was defined on. By using call(), apply() and bind(), we can easily borrow methods from different objects without having to inherit from them.

Now let’s make one more minor improvement in the hashing function:

function hash(args) {

return args[0] + ',' + args[1];

}

As of now, it works only on two arguments. It would be better if it could glue any number of args.

The natural solution would be to use arr.join method:

function hash() {

alert( arguments.join() ); // Error: arguments.join is not a function

}

hash(1, 2);

…Unfortunately, that won’t work. Because we are calling hash(arguments) and arguments object is both iterable and array-like, but not a real array. So calling join on it would fail.

Still, there’s an easy way to use array join:

function hash() {

alert( [].join.call(arguments) ); // 1,2

}

hash(1, 2);

The trick is called Method Borrowing. We take (borrow) a join method from a regular array [].join. And use [].join.call to run it in the context of the object arguments.

To grasp the concept of Method Borrowing let's continue.

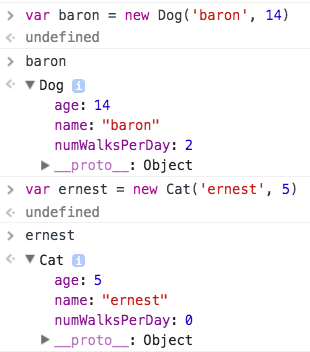

Let’s look at the following two functions as an example:

function Dog(name, age){

this.name = name;

this.age = age;

this.numWalksPerDay = 2;

}

function Cat(name,age){

this.name = name;

this.age = age;

this.numWalksPerDay = 0;

}

Nothing out-of-the-ordinary here. Just two rather simple constructor functions that can be used to create Dog and Cat objects. Creating objects with these is done with the ‘new’ keyword.

The only issue is that we have to repeat the ‘name’ and ‘age’ attributes for each object. Not very DRY. It would be nice if we could somehow use the attributes defined in the Dog function and apply them to the Cat function. That way, they are only defined once but can be used in as many places as necessary. Luckily, this is where methods like .call() come in.

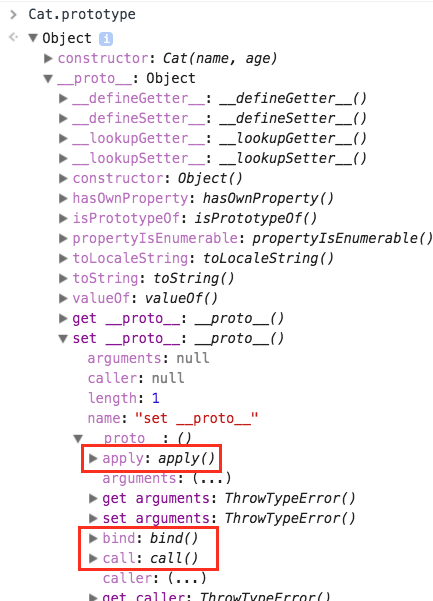

The unique thing about the .call(), .apply(), and .bind() functions is that they are methods on the prototype attribute of an object. If you look at the prototype of an object and dig far enough into its prototype chain, then you will see these methods defined.

These methods also allow you to define the context of the ‘this’ keyword and that is what makes it possible to ‘borrow’ attributes from one function and use them in another. If we were to just add the Dog function as part of the Cat function, this would not work because ‘this’ would have the wrong context.

However , we can do this if we redefine the context of ‘this’ using one of the prototype methods. This will then change ‘this’ to be the context of the object being created from the constructor. But how do we redefine ‘this’? With ‘this’. In this case in order to define the context of ‘this’ we need to pass the ‘call’ method the keyword of ‘this’ so that the context is set to the object that is being created.

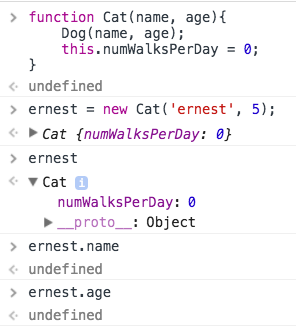

Let’s take this step-by-step. You already know that this example won’t work:

function Cat(name, age){

Dog(name, age);

this.numWalksPerDay = 0;

}

It won’t work because the object being created from the Cat constructor has no idea what Dog is and thus can’t use any of its attributes. Okay, what about using .call() to define the context?

function Cat(name, age){

Dog.call(Dog, name, age);

this.numWalksPerDay = 0;

}

Nope, the result is the same. The .call() method is still just setting the ‘this’ context to be that of the Dog constructor and the new Cat object being created won’t be aware of that.

What needs to be done is to explicitly set the context of ‘this’ to the object that is being created.

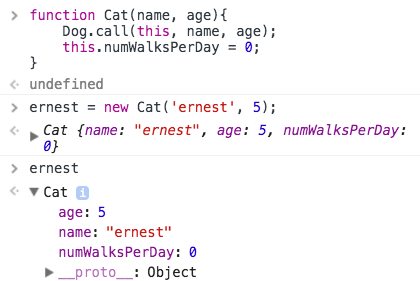

function Cat(name, age){

Dog.call(this, name, age);

this.numWalksPerDay = 0;

}

I think of this as being a substitute for the ‘this.name = name; this.age = age’ lines in the original constructor. But rather than writing those same lines again in the Cat constructor, you are looking to the Dog constructor for them.

So, now our two constructor functions look like this:

function Dog(name, age){

this.name = name;

this.age = age;

this.numWalksPerDay = 2;

}

function Cat(name,age){

Dog.call(this, name, age);

this.numWalksPerDay = 0;

}

Since the name and age attributes are shared between these two constructors you can make them DRY by using a prototype method like .call() to reuse code from one constructor to another.

Coming to our example, let's see how our below example works -

function hash() {

alert( [].join.call(arguments) ); // 1,2

}

hash(1, 2);

Here arguments object is iterable and array-like objects but not a real array. And most array methods are written in such a way that they can be used on iterable, array, array-like etc. All you have to do it is to borrow the method and call the method in the context of the object on which you are going to use it.

Example : 1

let obj = {

0 : 1,

1 : 2,

2 : 3,

'length' : 3

};

console.log([].join.call(obj)); // 1,2,3

Example : 2

function name(firstName, lastName){

this.firstName = firstName;

this.lastName = lastName;

this.fullName = function(){

return this.firstName + " " + this.lastName;

};

}

function user(firstName, lastName, age){

this.firstName = firstName;

this.lastName = lastName;

this.age = age;

}

let santanu = new user('Santanu', 'Bera', 30);

let hisName = new name("Lorem", 'Ipsum');

console.log(hisName.fullName.call(santanu)); // Santanu Bera

Note that, the method fullName is not defined on the function user. What we did, we borrowed the method from the function name and used that method in the context of the object santanu. It is like if santanu had the method fullName defined.

Function binding

When using setTimeout with object methods or passing object methods along, there’s a known problem: "losing this". We already know that in JavaScript it’s easy to lose this. Once a method is passed somewhere separately from the object – this is lost.

let user = {

firstName: "John",

sayHi() {

alert(`Hello, ${this.firstName}!`);

}

};

setTimeout(user.sayHi, 1000); // Hello, undefined!

As we can see, the output shows not “John” as this.firstName, but undefined. That’s because setTimeout got the function user.sayHi, separately from the object. The last line can be rewritten as.

let f = user.sayHi; setTimeout(f, 1000); // lost user context

The task is quite typical – we want to pass an object method somewhere else (here – to the scheduler) where it will be called. How to make sure that it will be called in the right context?

Solution 1: a wrapper

The simplest solution is to use a wrapping function:

let user = {

firstName: "John",

sayHi() {

alert(`Hello, ${this.firstName}!`);

}

};

setTimeout(function() {

user.sayHi(); // Hello, John!

}, 1000);

Now it works, because it receives user from the outer lexical environment, and then calls the method normally.

But, what if before setTimeout triggers (there’s one second delay!) user changes value? Then, suddenly, it will call the wrong object!

let user = {

firstName: "John",

sayHi() {

alert(`Hello, ${this.firstName}!`);

}

};

setTimeout(() => user.sayHi(), 1000);

// ...within 1 second

user = { sayHi() { alert("Another user in setTimeout!"); } };

// Another user in setTimeout?!?

The next solution guarantees that such thing won’t happen.

Solution 2: bind

Functions provide a built-in method bind that allows to fix this.

// more complex syntax will be little later let boundFunc = func.bind(context);

The result of func.bind(context) is a special function-like “exotic object”, that is callable as function and transparently passes the call to func setting this=context. For instance, here funcUser passes a call to func with this=user:

let user = {

firstName: "John"

};

function func() {

alert(this.firstName);

}

let funcUser = func.bind(user);

funcUser(); // John

All arguments are passed to the original func “as is”, for instance:

let user = {

firstName: "John"

};

function func(phrase) {

alert(phrase + ', ' + this.firstName);

}

// bind this to user

let funcUser = func.bind(user);

funcUser("Hello"); // Hello, John (argument "Hello" is passed, and this=user)

Now let’s try with an object method:

let user = {

firstName: "John",

sayHi() {

alert(`Hello, ${this.firstName}!`);

}

};

let sayHi = user.sayHi.bind(user); // (*)

sayHi(); // Hello, John!

setTimeout(sayHi, 1000); // Hello, John!

In the line (*) we take the method user.sayHi and bind it to user. The sayHi is a “bound” function, that can be called alone or passed to setTimeout – doesn’t matter, the context will be right.

Here we can see that arguments are passed “as is”, only this is fixed by bind:

let user = {

firstName: "John",

say(phrase) {

alert(`${phrase}, ${this.firstName}!`);

}

};

let say = user.say.bind(user);

say("Hello"); // Hello, John ("Hello" argument is passed to say)

say("Bye"); // Bye, John ("Bye" is passed to say)

Bind Arguments

Until now we have only been talking about binding this. Let’s take it a step further. We can bind not only this, but also arguments. That’s rarely done, but sometimes can be handy. The full syntax of bind:

let bound = func.bind(context, arg1, arg2, ...);

It allows to bind context as this and starting arguments of the function. For instance, we have a multiplication function mul(a, b):

function mul(a, b) {

return a * b;

}

Let’s use bind to create a function double on its base:

let double = mul.bind(null, 2); alert( double(3) ); // = mul(2, 3) = 6 alert( double(4) ); // = mul(2, 4) = 8 alert( double(5) ); // = mul(2, 5) = 10

The call to mul.bind(null, 2) creates a new function double that passes calls to mul, fixing null as the context and 2 as the first argument. Further arguments are passed “as is”.

That’s called partial function application – we create a new function by fixing some parameters of the existing one.

Please note that here we actually don’t use this here. But bind requires it, so we must put in something like null.

The function triple in the code below triples the value:

let triple = mul.bind(null, 3); alert( triple(3) ); // = mul(3, 3) = 9 alert( triple(4) ); // = mul(3, 4) = 12 alert( triple(5) ); // = mul(3, 5) = 15

Why do we usually make a partial function?

Here our benefit is that we created an independent function with a readable name (double, triple). We can use it and don’t write the first argument of every time, cause it’s fixed with bind.

In other cases, partial application is useful when we have a very generic function, and want a less universal variant of it for convenience.

For instance, we have a function send(from, to, text). Then, inside a user object we may want to use a partial variant of it: sendTo(to, text) that sends from the current user.

Going partial without context

What if we’d like to fix some arguments, but not bind this? The native bind does not allow that. We can’t just omit the context and jump to arguments. Fortunately, a partial function for binding only arguments can be easily implemented.

function partial(func, ...argsBound) {

return function(...args) { // (*)

return func.call(this, ...argsBound, ...args);

}

}

// Usage:

let user = {

firstName: "John",

say(time, phrase) {

alert(`[${time}] ${this.firstName}: ${phrase}!`);

}

};

// add a partial method that says something now by fixing the first argument

user.sayNow = partial(user.say, new Date().getHours() + ':' + new Date().getMinutes());

user.sayNow("Hello");

// Something like:

// [10:00] John: Hello!

The result of partial(func[, arg1, arg2...]) call is a wrapper (*) that calls func with:

- Same

thisas it gets (foruser.sayNowcall it’suser) - Then gives it

...argsBound– arguments from the partial call ("10:00") - Then gives it

...args– arguments given to the wrapper ("Hello")

Also there’s a ready _.partial implementation from lodash library.