Recursion

The function that calls itself is called Recursion function. Instead of using recursion function you can also use loop but there are crertain situation where Recursion function plays the best role and plays efficiently.

Consider the following example. In the following example we are calculating the exponential of a value. Here is the version using loop -

function pow(x, n) {

let result = 1;

// multiply result by x n times in the loop

for (let i = 0; i < n; i++) {

result *= x;

}

return result;

}

alert( pow(2, 3) ); // 8

The following version uses recursive function -

function pow(x, n) {

if (n == 1) {

return x;

} else {

return x * pow(x, n - 1);

}

}

alert( pow(2, 3) ); // 8

You can even make it more shorter -

function pow(x, n) {

return (n == 1) ? x : (x * pow(x, n - 1));

}

alert( pow(2, 3) ); // 8

As you can see, the recursive functions are easy to read, and can be done with less code.

Recursive traversals

Another great application of the recursion is a recursive traversal. Imagine, we have a company. The staff structure can be presented as an object:

let company = {

sales: [{

name: 'John',

salary: 1000

}, {

name: 'Alice',

salary: 600

}],

development: {

sites: [{

name: 'Peter',

salary: 2000

}, {

name: 'Alex',

salary: 1800

}],

internals: [{

name: 'Jack',

salary: 1300

}]

}

};

In other words, a company has departments. A department may have an array of staff. For instance, sales department has 2 employees: John and Alice. Or a department may split into subdepartments, like development has two branches: sites and internals. Each of them has the own staff. It is also possible that when a subdepartment grows, it divides into subsubdepartments (or teams). For instance, the sites department in the future may be split into teams for siteA and siteB. And they, potentially, can split even more.

Now let’s say we want a function to get the sum of all salaries. How can we do that?

An iterative approach is not easy, because the structure is not simple. The first idea may be to make a for loop over company with nested subloop over 1st level departments. But then we need more nested subloops to iterate over the staff in 2nd level departments like sites. …And then another subloop inside those for 3rd level departments that might appear in the future? Should we stop on level 3 or make 4 levels of loops? If we put 3-4 nested subloops in the code to traverse a single object, it becomes rather ugly.

Let’s try recursion. As we can see, when our function gets a department to sum, there are two possible cases:

- Either it’s a “simple” department with an array of people – then we can sum the salaries in a simple loop.

- Or it’s an object with N subdepartments – then we can make N recursive calls to get the sum for each of the subdeps and combine the results.

let company = { // the same object, compressed for brevity

sales: [{name: 'John', salary: 1000}, {name: 'Alice', salary: 600 }],

development: {

sites: [{name: 'Peter', salary: 2000}, {name: 'Alex', salary: 1800 }],

internals: [{name: 'Jack', salary: 1300}]

}

};

// The function to do the job

function sumSalaries(department) {

if (Array.isArray(department)) { // case (1)

return department.reduce((prev, current) => prev + current.salary, 0); // sum the array

} else { // case (2)

let sum = 0;

for (let subdep of Object.values(department)) {

sum += sumSalaries(subdep); // recursively call for subdepartments, sum the results

}

return sum;

}

}

alert(sumSalaries(company)); // 6700

The code is short and easy to understand. That’s the power of recursion. It also works for any level of subdepartment nesting.

Rest parameters

Rest parameters allows us to call a method with any number of arguments. Rest parameter is specified as ... (three dots together). Consider the following -

function sum(a, b) {

return a + b;

}

alert( sum(1, 2, 3, 4, 5) );

There will be no error because of “excessive” arguments. But of course in the result only the first two will be counted. The rest parameters can be mentioned in a function definition with three dots .... They literally mean “gather the remaining parameters into an array”.

function sumAll(...args) { // args is the name for the array

let sum = 0;

for (let arg of args) sum += arg;

return sum;

}

alert( sumAll(1) ); // 1

alert( sumAll(1, 2) ); // 3

alert( sumAll(1, 2, 3) ); // 6

We can choose to get the first parameters as variables, and gather only the rest. Here the first two arguments go into variables and the rest go into titles array:

function showName(firstName, lastName, ...titles) {

alert( firstName + ' ' + lastName ); // Julius Caesar

// the rest go into titles array

// i.e. titles = ["Consul", "Imperator"]

alert( titles[0] ); // Consul

alert( titles[1] ); // Imperator

alert( titles.length ); // 2

}

showName("Julius", "Caesar", "Consul", "Imperator");

The rest parameters must be at the end

The rest parameters gather all remaining arguments, so the following does not make sense and causes an error:

function f(arg1, ...rest, arg2) { // arg2 after ...rest ?!

// error

}

The ...rest must always be last.

The “arguments” variable

There is also a special array-like object named arguments that contains all arguments by their index.

function showName() {

alert( arguments.length );

alert( arguments[0] );

alert( arguments[1] );

// it's iterable

// for(let arg of arguments) alert(arg);

}

// shows: 2, Julius, Caesar

showName("Julius", "Caesar");

// shows: 1, Ilya, undefined (no second argument)

showName("Ilya");

In old times, rest parameters did not exist in the language, and using arguments was the only way to get all arguments of the function, no matter their total number. And it still works, we can use it today. But the downside is that although arguments is both array-like and iterable, it’s not an array. It does not support array methods, so we can’t call arguments.map(...) for example.

Arrow functions do not have "arguments"

If we access the arguments object from an arrow function, it takes them from the outer “normal” function.

function f() {

let showArg = () => alert(arguments[0]);

showArg();

}

f(1); // 1

If you pass any arguments in the arrow function and you try to access them using arguments object, you won't get the correct result. Arrow function gets the arguments object from the outer context in which the arrow function is defined.

Spread operator

We’ve just seen how to get an array from the list of parameters. But sometimes we need to do exactly the reverse. For instance, there’s a built-in function Math.max that returns the greatest number from a list:

alert( Math.max(3, 5, 1) ); // 5

Now let’s say we have an array [3, 5, 1]. How do we call Math.max with it? Passing it “as is” won’t work, because Math.max expects a list of numeric arguments, not a single array:

let arr = [3, 5, 1]; alert( Math.max(arr) ); // NaN

And surely we can’t manually list items in the code Math.max(arr[0], arr[1], arr[2]), because we may be unsure how many there are. As our script executes, there could be a lot, or there could be none. And that would get ugly. Spread operator to the rescue! It looks similar to rest parameters, also using ..., but does quite the opposite.

When ...arr is used in the function call, it “expands” an iterable object arr into the list of arguments.

let arr = [3, 5, 1]; alert( Math.max(...arr) ); // 5 (spread turns array into a list of arguments)

We also can pass multiple iterables this way:

let arr1 = [1, -2, 3, 4]; let arr2 = [8, 3, -8, 1]; alert( Math.max(...arr1, ...arr2) ); // 8

We can even combine the spread operator with normal values:

let arr1 = [1, -2, 3, 4]; let arr2 = [8, 3, -8, 1]; alert( Math.max(1, ...arr1, 2, ...arr2, 25) ); // 25

Merging Array

Also, the spread operator can be used to merge arrays:

let arr = [3, 5, 1]; let arr2 = [8, 9, 15]; let merged = [0, ...arr, 2, ...arr2]; alert(merged); // 0,3,5,1,2,8,9,15 (0, then arr, then 2, then arr2)

Spread Operator Works on any Iterator

In the examples above we used an array to demonstrate the spread operator, but any iterable will do. For instance, here we use the spread operator to turn the string into array of characters:

let str = "Hello"; alert( [...str] ); // H,e,l,l,o

The spread operator internally uses iterators to gather elements, the same way as for..of does.

So, for a string, for..of returns characters and ...str becomes "H","e","l","l","o". The list of characters is passed to array initializer [...str].

Array.from Vs Spread Operator

Array.from() can be used to make an array from Object, String etc.

let str = "Bera"; let arr = Array.from(str); // ['B', 'e', 'r', 'a']

You can alos use spead operator to convert an Iterable to an array -

let str = "Bera"; let arr = [...str]; // ['B', 'e', 'r', 'a']

But there’s a subtle difference between Array.from(obj) and [...obj]:

Array.fromoperates on both array-likes and iterables.- The spread operator operates only on iterables.

So, for the task of turning something into an array, Array.from tends to be more universal.

Closure

There is a general programming term “closure”, that developers generally should know.

A closure is a function that remembers its outer variables and can access them. In some languages, that’s not possible, or a function should be written in a special way to make it happen. But as explained above, in JavaScript, all functions are naturally closures (there is only one exclusion, to be covered in The "new Function" syntax). That is:

They automatically remember where they were created using a hidden [[Environment]] property, and all of them can access outer variables.

JavaScript is a very function-oriented language. It gives us a lot of freedom. A function can be created at one moment, then copied to another variable or passed as an argument to another function and called from a totally different place later.

We know that a function can access variables outside of it; this feature is used quite often.

But what happens when an outer variable changes? Does a function get the most recent value or the one that existed when the function was created? Also, what happens when a function travels to another place in the code and is called from there – does it get access to the outer variables of the new place?

Different languages behave differently here, and in this chapter we cover the behaviour of JavaScript.

Let’s consider two situations to begin with, and then study the internal mechanics piece-by-piece, so that you’ll be able to answer the following questions and more complex ones in the future.

-

The function

sayHiuses an external variablename. When the function runs, which value is it going to use?let name = "John"; function sayHi() { alert("Hi, " + name); } name = "Pete"; sayHi(); // what will it show: "John" or "Pete"?Such situations are common both in browser and server-side development. A function may be scheduled to execute later than it is created, for instance after a user action or a network request.

So, the question is: does it pick up the latest changes?

-

The function

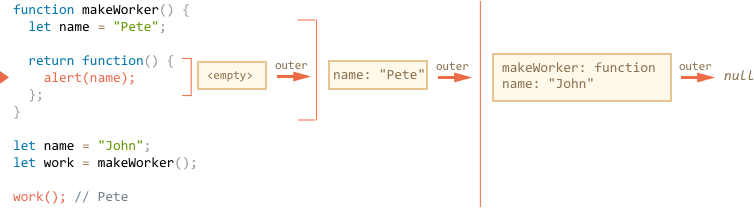

makeWorkermakes another function and returns it. That new function can be called from somewhere else. Will it have access to the outer variables from its creation place, or the invocation place, or both?function makeWorker() { let name = "Pete"; return function() { alert(name); }; } let name = "John"; // create a function let work = makeWorker(); // call it work(); // what will it show? "Pete" (name where created) or "John" (name where called)?

Lexical Environment

To understand what’s going on, let’s first discuss what a “variable” actually is. In JavaScript, every running function, code block, and the script as a whole have an associated object known as the Lexical Environment. The Lexical Environment object consists of two parts:

Environment Record– an object that has all local variables as its properties (and some other information like the value ofthis).- A reference to the outer lexical environment, usually the one associated with the code lexically right outside of it (outside of the current curly brackets).

So, a “variable” is just a property of the special internal object, Environment Record. “To get or change a variable” means “to get or change a property of the Lexical Environment”.

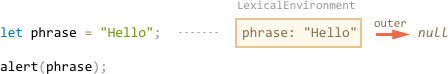

For instance, in this simple code, there is only one Lexical Environment:

This is a so-called global Lexical Environment, associated with the whole script. For browsers, all <script> tags share the same global environment.

On the picture above, the rectangle means Environment Record (variable store) and the arrow means the outer reference. The global Lexical Environment has no outer reference, so it points to null.

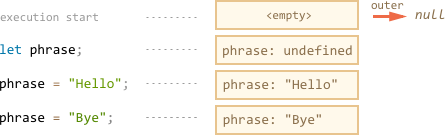

Here’s the bigger picture of how let variables work:

Rectangles on the right-hand side demonstrate how the global Lexical Environment changes during the execution:

- When the script starts, the Lexical Environment is empty.

- The

letphrase definition appears. It has been assigned no value, soundefinedis stored. phraseis assigned a value.phraserefers to a new value.

To summarize:

- A variable is a property of a special internal object, associated with the currently executing block/function/script.

- Working with variables is actually working with the properties of that object.

Function Declaration

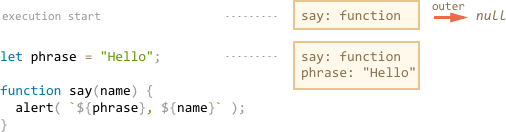

Function Declarations are special. Unlike let variables, they are processed not when the execution reaches them, but when a Lexical Environment is created. For the global Lexical Environment, it means the moment when the script is started. That is why we can call a function declaration before it is defined. The code below demonstrates that the Lexical Environment is non-empty from the beginning. It has say function, because that’s a Function Declaration. And later it gets phrase, declared with let:

Inner and outer Lexical Environment

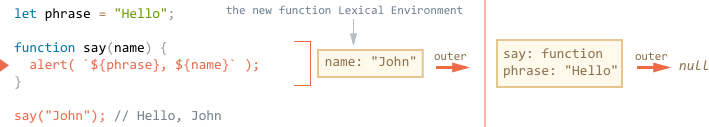

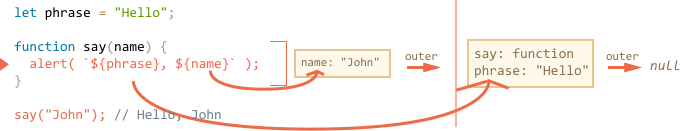

During the call, say() uses an outer variable, so let’s look at the details of what’s going on.

First, when a function runs, a new function Lexical Environment is created automatically. That’s a general rule for all functions. That Lexical Environment is used to store local variables and parameters of the call.

Here’s the picture of Lexical Environments when the execution is inside say("John"), at the line labelled with an arrow:

During the function call we have two Lexical Environments: the inner one (for the function call) and the outer one (global):

- The inner Lexical Environment corresponds to the current execution of say. It has a single variable:

name, the function argument. We calledsay("John"), so the value of name is "John". - The outer Lexical Environment is the global Lexical Environment.

The inner Lexical Environment has the outer reference to the outer one.

When code wants to access a variable – it is first searched for in the inner Lexical Environment, then in the outer one, then the more outer one and so on until the end of the chain.

If a variable is not found anywhere, that’s an error in strict mode. Without use strict, an assignment to an undefined variable creates a new global variable, for backwards compatibility.

Let’s see how the search proceeds in our example:

- When the

alertinsidesaywants to accessname, it finds it immediately in the function Lexical Environment. - When it wants to access

phrase, then there is nophraselocally, so it follows the outer reference and finds it globally.

Now we can give the answer to the first question from the beginning of the chapter.

A function gets outer variables as they are now; it uses the most recent values.

That’s because of the described mechanism. Old variable values are not saved anywhere. When a function is called, it takes the current values from its own or an outer Lexical Environment.

So the answer to the first question is Pete:

let name = "John";

function sayHi() {

alert("Hi, " + name);

}

name = "Pete"; // (*)

sayHi(); // Pete

The execution flow of the code above:

- The global Lexical Environment has

name: "John". - At the line (*) the global variable is changed, now it has

name: "Pete". - When the function

sayHi(), is executed and takesnamefrom outside. Here that’s from the global Lexical Environment where it’s already"Pete".

One call – one Lexical Environment

Please note that a new function Lexical Environment is created each time a function runs. And if a function is called multiple times, then each invocation will have its own Lexical Environment, with local variables and parameters specific for that very run.

Nested functions

A function is called “nested” when it is created inside another function. It is easily possible to do this with JavaScript. We can use it to organize our code, like this:

function sayHiBye(firstName, lastName) {

// helper nested function to use below

function getFullName() {

return firstName + " " + lastName;

}

alert( "Hello, " + getFullName() );

alert( "Bye, " + getFullName() );

}

What’s more interesting, a nested function can be returned: either as a property of a new object (if the outer function creates an object with methods) or as a result by itself. It can then be used somewhere else. No matter where, it still has access to the same outer variables. An example with the constructor function:

// constructor function returns a new object

function User(name) {

// the object method is created as a nested function

this.sayHi = function() {

alert(name);

};

}

let user = new User("John");

user.sayHi(); // the method code has access to the outer "name"

An example with returning a function:

function makeCounter() {

let count = 0;

return function() {

return count++; // has access to the outer counter

};

}

let counter = makeCounter();

alert( counter() ); // 0

alert( counter() ); // 1

alert( counter() ); // 2

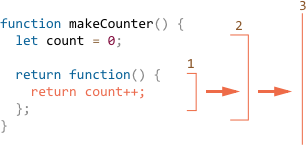

Let’s go on with the makeCounter example. It creates the “counter” function that returns the next number on each invocation. When the inner function runs, the variable in count++ is searched from inside out. For the example above, the order will be:

- The locals of the nested function…

- The variables of the outer function…

- And so on until it reaches global variables.

In this example count is found on step 2. When an outer variable is modified, it’s changed where it’s found. So count++ finds the outer variable and increases it in the Lexical Environment where it belongs.

Here are two questions to consider:

- Can we somehow reset the

counterfrom the code that doesn’t belong tomakeCounter? E.g. afteralertcalls in the example above. - If we call

makeCounter()multiple times – it returns manycounterfunctions. Are they independent or do they share the samecount?

The answers are -

- There is no way. The

counteris a local function variable, we can’t access it from the outside. - For every call to

makeCounter()a new function Lexical Environment is created, with its owncounter. So the resultingcounterfunctions are independent.

function makeCounter() {

let count = 0;

return function() {

return count++;

};

}

let counter1 = makeCounter();

let counter2 = makeCounter();

alert( counter1() ); // 0

alert( counter1() ); // 1

alert( counter2() ); // 0 (independent)

Environments in detail

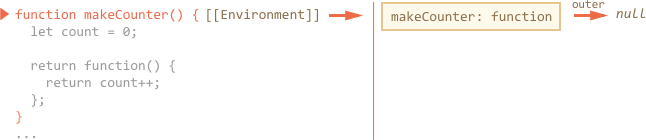

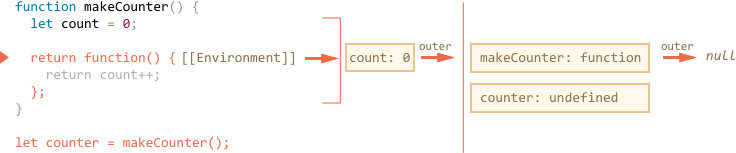

Now that you understand how closures work generally, we can descend to the very nuts and bolts. Here’s what’s going on in the makeCounter example step-by-step, follow it to make sure that you understand everything. Please note the additional [[Environment]] property that we didn’t cover yet.

-

When the script has just started, there is only global Lexical Environment:

At that starting moment there is only

makeCounterfunction, because it’s a Function Declaration. It did not run yet. All functions “on birth” receive a hidden property[[Environment]]with a reference to the Lexical Environment of their creation. We didn’t talk about it yet, but that’s how the function knows where it was made.Here,

makeCounteris created in the global Lexical Environment, so[[Environment]]keeps a reference to it.In other words, a function is “imprinted” with a reference to the Lexical Environment where it was born. And

[[Environment]]is the hidden function property that has that reference. -

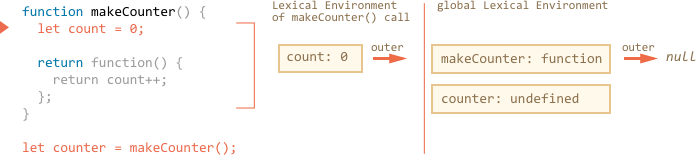

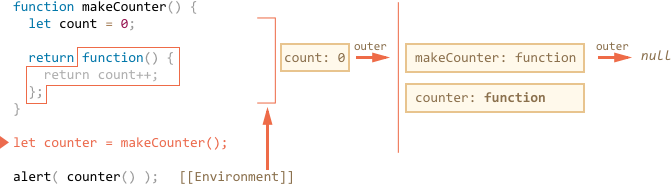

The code runs on, the new global variable counter is declared and for its value

makeCounter()is called. Here’s a snapshot of the moment when the execution is on the first line insidemakeCounter():

At the moment of the call of

makeCounter(), the Lexical Environment is created, to hold its variables and arguments. As all Lexical Environments, it stores two things:- An Environment Record with local variables. In our case

countis the only local variable (appearing when the line withlet countis executed). - The outer lexical reference, which is set to

[[Environment]]of the function. Here[[Environment]]ofmakeCounterreferences the global Lexical Environment.

So, now we have two Lexical Environments: the first one is global, the second one is for the current

makeCountercall, with the outer reference to global. - An Environment Record with local variables. In our case

-

During the execution of

makeCounter(), a tiny nested function is created. It doesn’t matter whether the function is created using Function Declaration or Function Expression. All functions get the[[Environment]]property that references the Lexical Environment in which they were made. So our new tiny nested function gets it as well.For our new nested function the value of

[[Environment]]is the current Lexical Environment ofmakeCounter()(where it was born):

Please note that on this step the inner function was created, but not yet called. The code inside

function() { return count++; }is not running; we’re going to return it soon. -

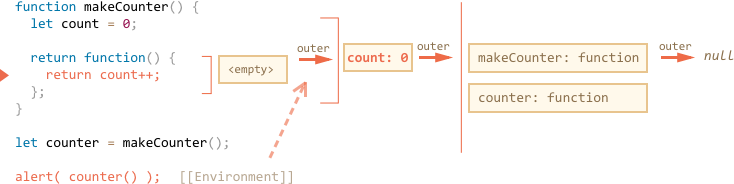

As the execution goes on, the call to

makeCounter()finishes, and the result (the tiny nested function) is assigned to the global variablecounter:

That function has only one line:

return count++, that will be executed when we run it. -

When the

counter()is called, an “empty” Lexical Environment is created for it. It has no local variables by itself. But the[[Environment]]ofcounteris used as the outer reference for it, so it has access to the variables of the formermakeCounter()call where it was created:

-

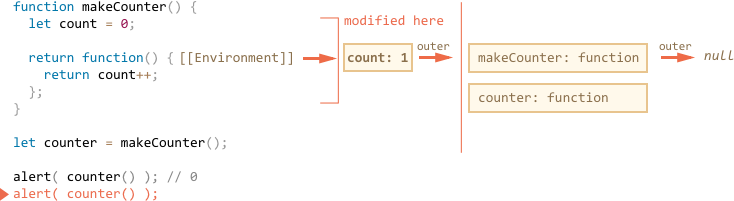

The call to

counter()not only returns the value ofcount, but also increases it. Note that the modification is done “in place”. The value ofcountis modified exactly in the environment where it was found.

So we return to the previous step with the only change – the new value of

count.

Now if it accesses a variable, it first searches its own Lexical Environment (empty), then the Lexical Environment of the former makeCounter() call, then the global one.

Please note how memory management works here. Although makeCounter() call finished some time ago, its Lexical Environment was retained in memory, because there’s a nested function with [[Environment]] referencing it. Generally, a Lexical Environment object lives as long as there is a function which may use it. And only when there are none remaining, it is cleared.

The answer to the second question from the beginning of the chapter should now be obvious. The work() function in the code below uses the name from the place of its origin through the outer lexical environment reference:

So, the result is "Pete" here. But if there were no let name in makeWorker(), then the search would go outside and take the global variable as we can see from the chain above. In that case it would be "John".

Lexical Environment for Code blocks and loops, IIFE

The examples above concentrated on functions. But Lexical Environments also exist for code blocks {...}. They are created when a code block runs and contain block-local variables. Here are a couple of examples.

If

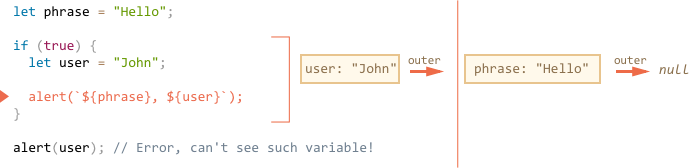

In the example below, when the execution goes into if block, the new “if-only” Lexical Environment is created for it:

The new Lexical Environment gets the enclosing one as the outer reference, so phrase can be found. But all variables and Function Expressions declared inside if reside in that Lexical Environment and can’t be seen from the outside.

For instance, after if finishes, the alert below won’t see the user, hence the error.

For, while

For a loop, every iteration has a separate Lexical Environment. If a variable is declared in for, then it’s also local to that Lexical Environment:

for (let i = 0; i < 10; i++) {

// Each loop has its own Lexical Environment

// {i: value}

}

alert(i); // Error, no such variable

That’s actually an exception, because let i is visually outside of {...}. But in fact each run of the loop has its own Lexical Environment with the current i in it.

Code blocks

We also can use a “bare” code block {…} to isolate variables into a “local scope”. For instance, in a web browser all scripts share the same global area. So if we create a global variable in one script, it becomes available to others. But that becomes a source of conflicts if two scripts use the same variable name and overwrite each other. That may happen if the variable name is a widespread word, and script authors are unaware of each other. If we’d like to avoid that, we can use a code block to isolate the whole script or a part of it:

{

// do some job with local variables that should not be seen outside

let message = "Hello";

alert(message); // Hello

}

alert(message); // Error: message is not defined

The code outside of the block (or inside another script) doesn’t see variables inside the block, because the block has its own Lexical Environment.

IIFE

In old scripts, one can find so-called “immediately-invoked function expressions” (abbreviated as IIFE) used for this purpose. They look like this:

(function() {

let message = "Hello";

alert(message); // Hello

})();

Here a Function Expression is created and immediately called. So the code executes right away and has its own private variables.

The Function Expression is wrapped with parenthesis (function {...}), because when JavaScript meets "function" in the main code flow, it understands it as the start of a Function Declaration. But a Function Declaration must have a name, so there will be an error:

// Error: Unexpected token (

function() { // <-- JavaScript cannot find function name, meets ( and gives error

let message = "Hello";

alert(message); // Hello

}();

We can say “okay, let it be so Function Declaration, let’s add a name”, but it won’t work. JavaScript does not allow Function Declarations to be called immediately:

// syntax error because of brackets below

function go() {

}(); // <-- can't call Function Declaration immediately

So, parenthesis are needed to show JavaScript that the function is created in the context of another expression, and hence it’s a Function Expression. It needs no name and can be called immediately.

Garbage collection of Lexical Environment

Lexical Environment objects that we’ve been talking about are subject to the same memory management rules as regular values.

Usually, Lexical Environment is cleaned up after the function run. For instance:

function f() {

let value1 = 123;

let value2 = 456;

}

f();

Here two values are technically the properties of the Lexical Environment. But after f() finishes that Lexical Environment becomes unreachable, so it’s deleted from the memory.

…But if there’s a nested function that is still reachable after the end of f, then its [[Environment]] reference keeps the outer lexical environment alive as well:

function f() {

let value = 123;

function g() { alert(value); }

return g;

}

let g = f(); // g is reachable, and keeps the outer lexical environment in memory

A Lexical Environment object dies when it becomes unreachable: when no nested functions remain that reference it. In the code below, after g becomes unreachable, the value is also cleaned from memory;

function f() {

let value = 123;

function g() { alert(value); }

return g;

}

let g = f(); // while g is alive

// there corresponding Lexical Environment lives

g = null; // ...and now the memory is cleaned up